You can save BIG by understanding how to avoid the evil built-in gains tax that often applies when you convert your C corporation into an S corporation.

Let’s say you decided the S corporation is your preferred choice of entity. How do you change your C corporation into an S corporation without paying government-imposed double taxes?

You see, the law does not simply let you switch. You need to consider the built-in gains taxes, which tax professionals refer to using the acronym BIG.

Why BIG? Because when you hit one of the triggers for the built-in gains tax, you pay double taxes. And the potential for triggering this double tax is embedded for up to the first five years of the newly created S corporation.

For example, say you operate your C corporation on a cash basis. On the day you convert to the S corporation, your C corporation has patients, customers, or clients who have not paid their bills. Now, because of the conversion, they pay those monies to the S corporation, which collects them as built-in gain receivables subject to the double tax.

The double tax works like this:

The remaining 79 percent of the profits (the untaxed part) that reside in the S corporation now flow through to you, the owner. And tax law imposes taxes on your individual income at tax rates as high as 40.8 percent, depending on the nature of the monies causing the tax.

It’s likely that the BIG double tax has your attention. If so, you will be happy to know that this article can help you plan to reduce or (better yet) avoid the BIG tax! Let’s get started.

Setting the Stage

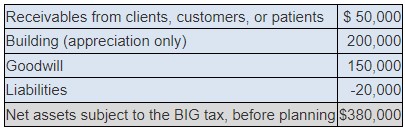

To give you a working knowledge of how the BIG tax works, we are going to use an example. Let’s say that your conversion from a C to an S corporation looks like this before you do any planning:

Here are four tax-saving strategies you can use to mitigate and perhaps even eliminate that nasty BIG double tax.

Strategy No. 1: Eliminate Goodwill

The BIG tax does not apply to goodwill if you refrain from selling your S corporation during the built-in gains penalty period (currently five years). The first strategy is to simply wait for the five years to elapse. That eliminates the goodwill problem.

Key point. Goodwill in this example is the profit embedded in the fair market value of the C corporation at the time of conversion to an S corporation. For you, this means that the fair market value of the C corporation at the time of conversion has the potential to trigger the BIG tax if you sell within five years.

How do you know that you won’t sell the business during the next five years or so? You can say you won’t, but you are not in total control—some unforeseen circumstance could disable or kill you and force the sale of the business.

To ensure avoidance of the BIG tax on goodwill, you need to plan before you convert the C corporation to an S corporation.

Before we move to that planning, let’s define “goodwill.” At the time you sell a business, goodwill is the excess value paid for the business over the net identifiable tangible and intangible assets.

You might attribute some goodwill to the company’s name, trademarks, patents, or location. But in most small businesses, the business owners themselves are the key reason clients, customers, and patients are attracted to the business. As a general rule, the more the business depends on the owner’s personal relationships, knowledge, skills, talent, reputation, or experience, the greater the personal goodwill.

This is where planning comes in. If the owner is the goodwill, then the goodwill is not a corporate asset. Instead, the goodwill is a personal asset owned by the business owner.1

The plan is to identify the personal goodwill at the time of conversion from a C to an S corporation. You don’t get to personally decide this. You need a proper appraisal of the goodwill so you can prove to the IRS the amount allocated to personal goodwill.

Again, remember, the BIG tax on goodwill becomes an issue only if

the goodwill is corporate goodwill, and

you sell the S corporation during the five-year BIG taxation period.

Strategy No. 2: Reduce Building Appreciation with an Accurate Appraisal

The BIG tax on appreciation of assets applies only to the appreciation that occurred prior to becoming an S corporation, and then only if you sell the asset during the BIG taxation period (currently five years from the date of conversion).

In this example, you have a building that looks like it has $200,000 of appreciation at the time you are going to convert your C corporation to an S corporation. How do you prove that it’s only $200,000?

You could assemble some of your own documents, but those documents obviously appear self-serving and likely don’t have great reliability. So what you really need—and don’t skip this step—is an accurate appraisal of the assets at the time of conversion to an S corporation.

Depending on the nature of the assets in the C corporation, you should choose an appraiser with credentials that the IRS will accept—someone with a designation such as

Accredited in Business Valuation (ABV), from the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA);

Accredited Senior Appraiser (ASA), from the American Society of Appraisers; or

Certified Valuation Analyst (CVA); from the National Association of Certified Valuation Analysts.

For real estate, works of art, and other specialized needs, you may need an appraiser with designations such as:2

Commercial Property Appraiser designation awarded by the Appraisal Institute (MAI)

Senior Residential Appraiser (SRA)

Senior Real Estate Appraiser (SREA)

Senior Real Property Appraiser (SRPA)

The appraiser will give you a lengthy valuation report detailing the valuation methods used and asset-by-asset listings with corresponding values.

Your plan to get an appraisal for less than $200,000 of building appreciation might include engaging multiple appraisers. Say you obtain a credible valuation that shows only $150,000 of appreciation. You just knocked $50,000 off your assets subject to the BIG tax while meeting the IRS’s burden of proof.

If you have an asset such as a building and you have a BIG tax problem once you consider all your strategies, it’s likely to be in your best interest to try for a lower appraisal.

Strategy No. 3: Give Yourself a Bonus

You’re reading this right—eliminate some of your tax by giving yourself money!

Even though your C corporation is on a cash basis, the built-in gains and losses include income and deduction items that would have been recognized by your cash-basis C corporation had it used the accrual method of accounting.3

So, just to clarify—neither your C corporation nor your S corporation uses the accrual method of accounting. But on the day you convert from a C corporation to an S corporation, the law makes your accounting pretend that you are on the accrual method. That’s why your cash-basis accounts receivable at the date of conversion are subject to the BIG tax.

So how does this rule of pretending to use accrual help you? If you documented that you were underpaid in prior years or that you deserve a bonus for the good work completed, you make those underpaid bonus amounts payable to yourself, and then have the S corporation pay them within two and a half months after conversion.4 As a result, you have a built-in loss to offset the built-in gains.

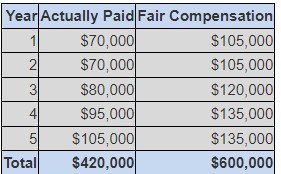

Example. You can prove that your C corporation underpaid you in the five years prior to electing S corporation status, and you establish an accrued liability to make up the pay deficit.

On the date of conversion, your S corporation recognizes the liability to pay the $180,000 shortfall and does, in fact, pay that shortfall within the first two and a half months after conversion. Presto! You have a $180,000 built-in loss.

Key point. Note that the compensation strategy requires payment within the first two and a half months after conversion. That means you should be planning your C-to-S-corporation conversion well before you elect S corporation status.

Strategy No. 4: Wait to Sell

The holding period to avoid the BIG tax is five years, which begins on the first day of the first taxable year that the law treats the C corporation as an S corporation.5 But one great bet is planning to avoid the tax altogether.

Why? Let’s look at our example.

Let’s say you made no plan other than to wait the five years. In Year 1, you would have a BIG tax on $30,000 because you collected the $50,000 of receivables and paid the $20,000 of liabilities.

That’s a tricky thing about the BIG tax: You recognize your built-in gains and losses on a year-by-year basis as you dispose of the assets or pay off the liabilities. For example, say you sold the building in Year 3 with no plan in place. You would face the BIG tax on $200,000 of appreciation.

The year-by-year recognition makes it less likely that you will avoid BIG tax problems with the “wait to sell” strategy. You are far better off with a plan to avoid the BIG tax on the date of conversion.

The Big Plan

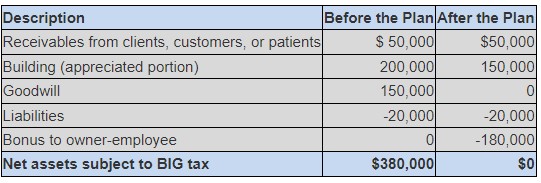

On the day you convert the C corporation to an S corporation, you tally the built-in gains and losses. The net built-in gain is the maximum amount subject to the BIG tax.6

As you can see in the chart above, your good planning thanks to this article gives you a net built-in gain of zero. That means you can collect the receivables and sell the building anytime without paying the big tax. This is a total escape.

Takeaways

The BIG tax is evil and nasty. But with proper planning, you can keep the BIG tax to a minimum and possibly eliminate it altogether.

Rule 1 is to absolutely know what the BIG problem is before converting your C corporation to an S corporation. Remember, the BIG tax is first 21 percent and then the regular tax on the remaining 79 percent. If you have $500,000 subject to the BIG tax and you are in the 37 percent regular tax bracket, your total tax is $251,150. That’s a 50 percent tax.

Your plan to reduce or eliminate the BIG tax (which is really a BIG double tax) might include some or all of the following: